12.10.2022

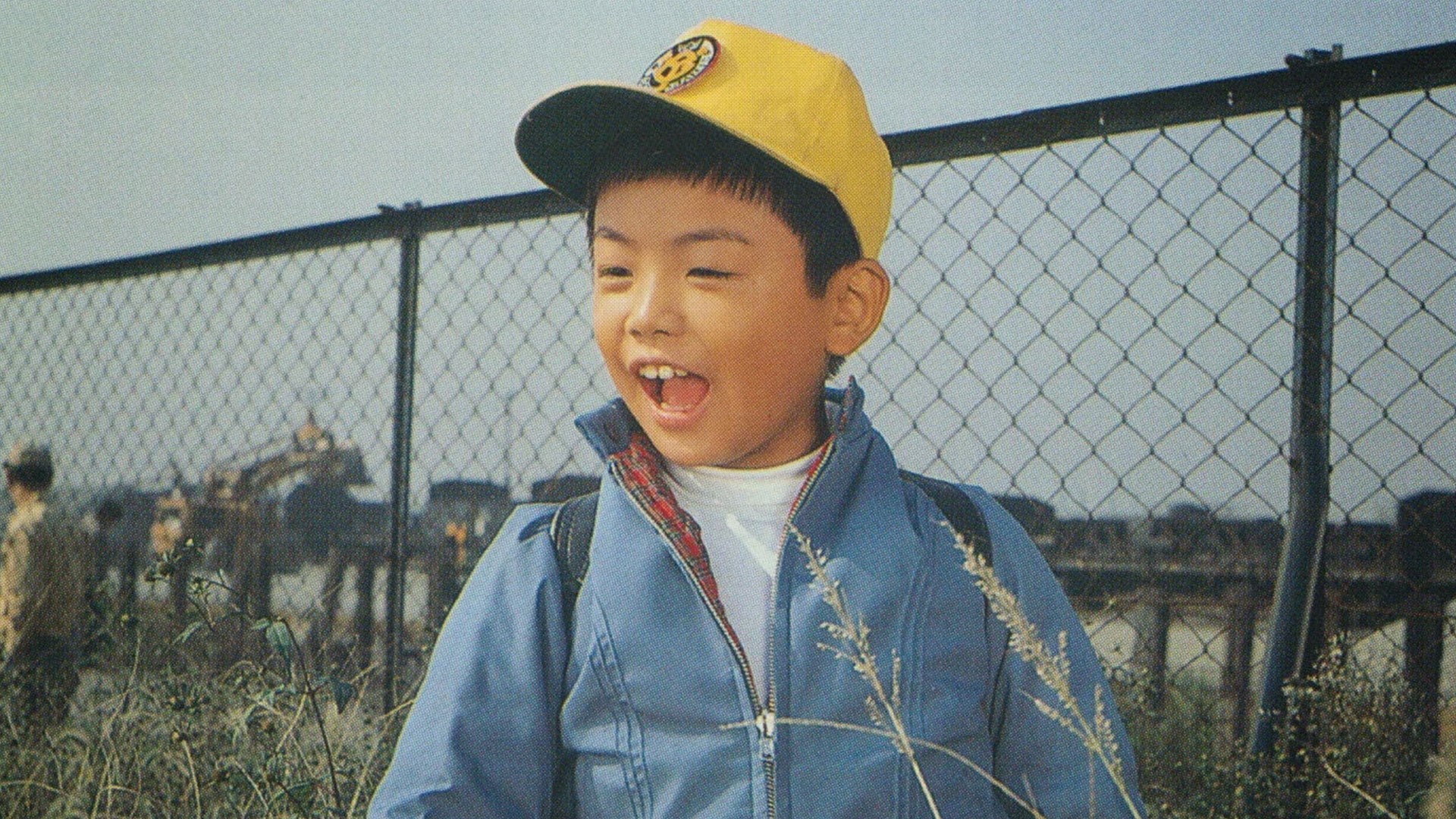

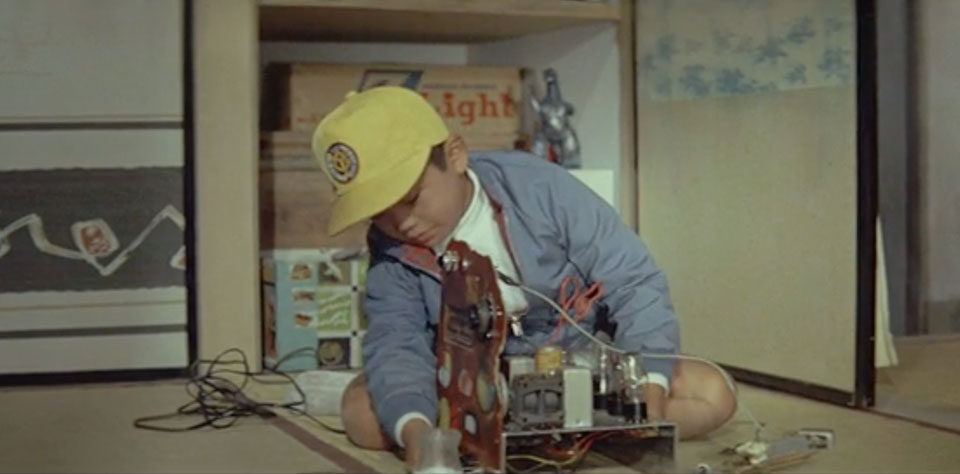

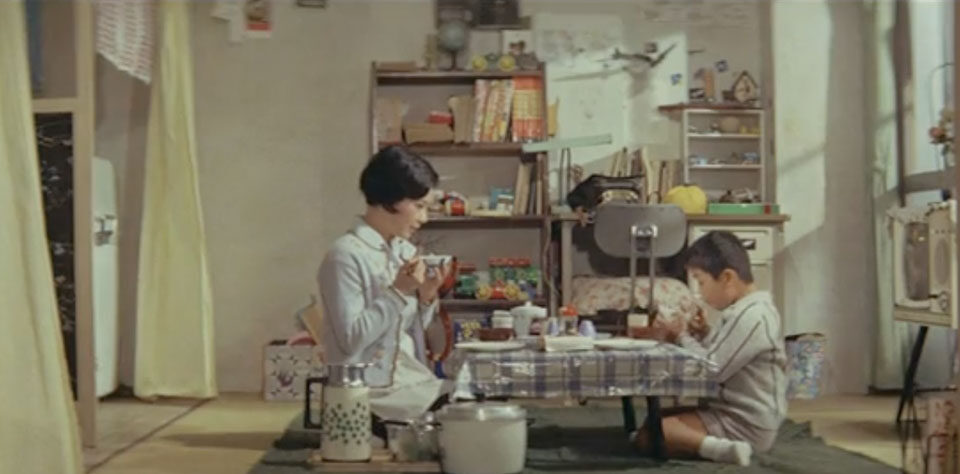

I love Godzilla’s Revenge (aka, Godzilla, Minya, and Gabara: All Monsters Attack, ゴジラ・ミニラ・ガバラ オール怪獣大進撃, released December 20, 1969) more everyday as I get older. Watching Ichiro reminds me of my childhood growing up with Godzilla. His imaginative play with his computer takes him to Monster Island but takes me back in time. Seeing his Marusan Shoten Godzilla figure in the background stirs up wonderful feelings from the past when life was much simpler and when it was just me and Godzilla. But there is another reason I love this movie. I have a strong affinity for his parent’s home and neighborhood. His home reminds me so much of the time I was living in Nagoya.