3.25.17

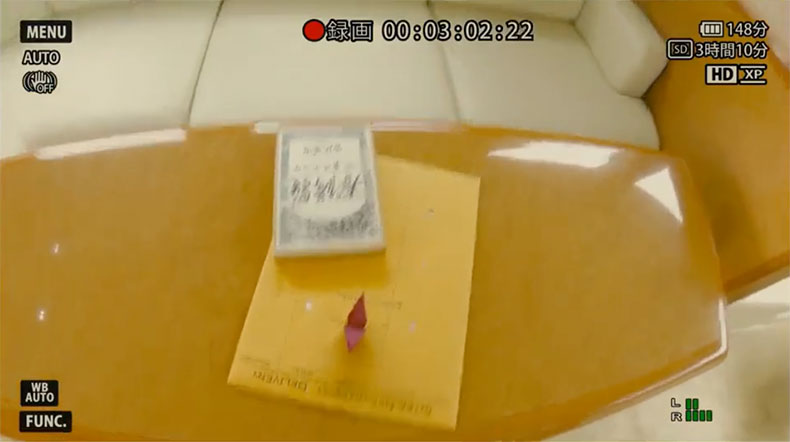

If you blinked, you missed it. Missed what you ask? The book left aboard the Glory Maru adrift in Tokyo Bay at the beginning of Shin Godzilla. Along with it was an envelope and a red origami crane atop a table beside an empty pair of shoes. The significance of the envelope’s content and the crane become readily clear as the film’s plot develops. However, the book’s significance would only be apparent to Japanese moviegoers acquainted with the book and the clues it provides into the mysterious Professor Goro Maki. This is not the case for us moviegoers who are not acquainted with the history of Japanese literature. And without research we certainly could not answer why he would leave this book behind and a hole would remain in our understand of the film.

After several hours of research and translation, the relationship between Prof Maki and the book is becoming more clear. After the opening scene there is no more reference to the book. We are left to piece together clues scattered throughout the film in order to understand Maki’s connection to the book left behind. As detailed in a previous blog post, Maki leaves behind Spring and Asura 『春と修羅』, an anthology of poems written by Kenji Miyazawa (宮沢 賢治). Miyazawa was born on August 27, 1896 in Hanamaki, Iwate, northern Japan. My Japanese friend, Kay Asano, said of him, “Kenji Miyazawa!! He is one of the most powerful poets in Japan ever!!” “His works,” he goes on to say, “is full of fantasy. His novel titled A night of Galaxy Express is his most popular one. Very sad and deep tale.” With this in mind what remains to be determined is the connection between Miyazawa and his book to Professor Maki.

In my research I came across two insightful articles: 1) 「『春と修羅』から見えてくるシン・ゴジラの核心 宮沢賢治と牧悟郎を結ぶもの」 (roughly translated, “The core of Shin Godzilla comes into view from “Spring and Shura: Connecting Kenji Miyazawa and Goro Maki”) by Shinoda Ikeda (池田 信太朗); and 2) “In harmony with all creation: It is 75 years since Kenji Miyazawa died, but his poetry and passion speaks to our lives today” by Roger Pulvers. From these I discovered two significant connections between Miyazawa and Maki.

First, both men suffered the tragic loss of a loved one. Pulvers writes, “The greatest tragedy in Miyazawa’s life was, without a doubt, the death from tuberculosis, at age 24, of his younger sister, Toshiko. One of the most famous Japanese poems of the 20th century is ‘The Morning of Last Farewell,’ in which Miyazawa describes the journey that his beloved sister will be taking on this day . . . You are truly bidding farewell on this day O my brave little sister Burning up pale white and gentle.” Miyazawa was in despair and her death marked the rest of his life and work. Pulvers goes on to say, “He is resigned to his sister’s death because he knows that she is now a part of everything that he sees before him.” It has been said that he never recovered from the traumatic shock of her death. The same can be say that of Maki stood on his pleasure craft looking into the water of Tokyo Bay. During the film, we learn from the research of the freelance reporter Tatsuya Hayafune, that Maki “mourned the death of his wife and “loathed the radiation sickness that took his wife’s life.” I believe Maki could no longer live without her for this reason he jumped into the sea in hope to soon join her once again.

Second, both men had a deep concern for nature and human responsibility. “Miyazawa believed, Pulvers writes, “that the spirit of Japanese people would die if they did not continue to recognize beauty and find happiness in concord with nature. Humans, birds, insects, all creatures pass on; and it is the trees and the light and the wind that transport their messages into the future.” Miyazawa was aware of the cost that Japan was paying for its new industrial power in his day. And Maki was aware of the cost Japan would pay for the reckless mishandling of radioactive waster by the nuclear industry. Although his words falls upon deaf ears, Prof Maki until his last breath is determined to warn the world of the dangers of the unregulated dumping of radioactive material and “to render radioactive material harmless.” The envelope left behind aboard his ship contained his scientific paper, “Inventory of Radioactive Material Entering the Marine Environment.” “It is presumed,” Maki writes, “that the containers of radioactive waste were hit by an unknown marine creature deep beneath the sea.” It is here that the film’s protagonist Rando Yaguchi learns of Godzilla and its birth connected to radioactive material. Maki had left his work and warning of the origin of Godzilla for the authorities who would desperately need his research.

The relationship between Miyazawa and Maki is deep. The work of both men would not be appreciated until after their death. Let us ponder both the life and work of both these men to better understand the message they left behind.